How to Write a Sci-Fi Novel

I had a fun chat with my longtime buddy Matt Conant about the process of writing a sci-fi novel.

How do fiction writers conjure up rich, novel imaginary worlds in their head? I’ve long been fascinated with the psychology of creative writing. In fact, that was my first book! So I was excited to chat with Matt Conant, a very imaginative and creative sci-fi writer.

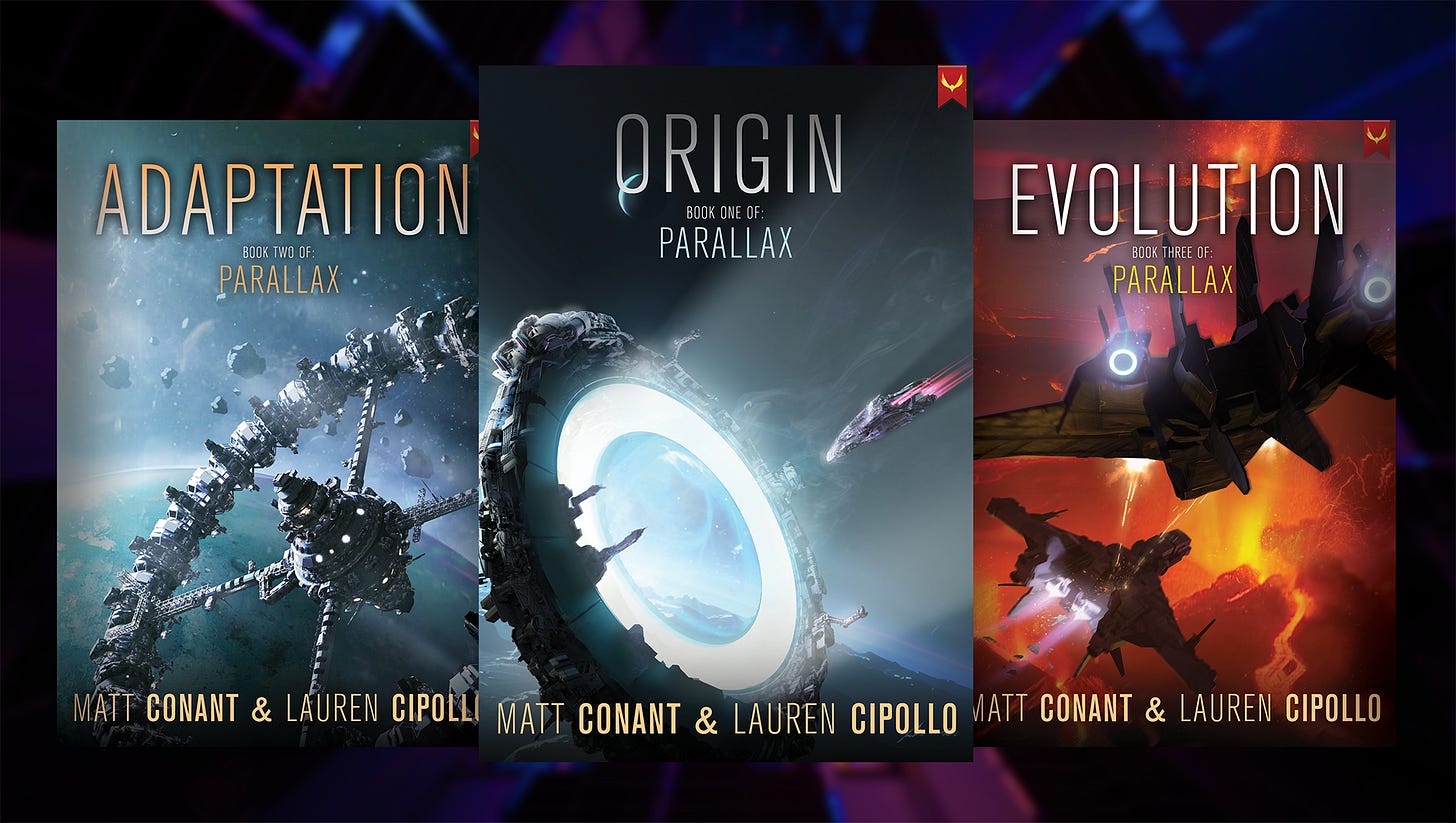

Matt Conant is a show creator, best-selling novelist, and award-winning screenwriter, specializing in comedy, sci-fi, and genre properties. He’s also a writer on the latest three seasons of MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER 3000. Through his production company, Cinevore Studios, Matt has optioned or sold TV projects to HBOMax, Amazon Studios, A&E Studios, and others. His debut novel, the space adventure PARALLAX: ORIGIN from Aethon Books is a #1 Amazon Bestseller in Science Fiction, and the follow-ups ADAPTATION and EVOLUTION are now available in ebook, paperback and audiobook. Originally from the Philadelphia suburbs, Matt now resides in Studio City, CA.

Oh, and by the way, I’ve known Matt since 6th grade and he’s a great guy. :)

Tell me about the process of writing a sci-fi novel?

I wrote the Parallax trilogy with my significant other and writing partner Lauren Cipollo. And I'm happy to describe the process we used, but wouldn't specifically recommend this one for anybody else. It's certainly not the way we've done it in any project since!

I'm primarily a screenwriter, and my background and degree is in Film. So it makes sense that Parallax began its life as a television pilot script I'd written many years ago, that basically sat on my shelf. Eventually, Lauren and I took the concept and began to develop it as a tabletop role-playing game, like Dungeons & Dragons, but set in our own original, hyper-capitalistic, gene-splicing, space-faring universe. We developed a species called Cygnans who are a sort of space druid, engineered to heal a beautiful planet that the corporations had destroyed.

From there, Lauren stumbled onto a character concept she loved and began to write a novel about a spaceship engineer. While she worked on that, I adapted my original pilot script from years earlier into a novel following a corporate Peacekeeper. We were both deeply steeped in the world, so we could help each other brainstorm and revise whenever we got stuck. After six months or so, we had two books with similar themes set in the same fictional universe during the same time period, but following different sets of characters. And honestly, mine was far too long, about a hundred and sixty thousand words. Eighty to a hundred thousand is generally recommended.

So we realized if we wanted to try to turn these into novels anybody would read, we'd want the characters to remain consistent throughout. So we did a fairly intense rewrite and restructuring, tying a lot of the plot points together between the books. Eventually, we had about three books worth of material, and one great overarching mystery into which all the characters were being drawn. We built Book 1 so that the chapters switch points of view between protagonists much the way Game of Thrones or The Expanse novels do. Then we edited each other's work so the pacing matched and the voice and tone would feel consistent throughout.

While we were restructuring the stories, we also had to change the structure within each book. These had been written as individual novels, so effectively splitting both of them into thirds and then shuffling them back together meant ensuring each character and each story had arcs that not only resolved over the course of the trilogy, but also that each book had enough of a climax and payoff to properly bring about some sort of catharsis for the reader.

In a normal situation, we would have had the final story all outlined first, and then simply switched off writing chapters in the first place. That might have saved us a year or two. But we couldn't be happier with how these books came together. From Goodreads and Amazon reviews, nobody seems to be able to see behind that curtain. Nobody notices which of us wrote which chapters, for instance, so that means we did our jobs as co-writers well.

What sort of creativity is involved?

That is a great question that nobody has ever asked me before, so I hope I have an answer for you. I feel like fiction writing involves different types of creativity in different stages of the process, and writing fantasy and science fiction possibly even moreso. I'm not a psychology expert, so I'll use what terms I think I've learned from being your friend and colleague over the years and hope I answer this correctly.

Every project I write starts with some real-life trigger that launches a brainstorming session. I've heard it referred to as Divergent Thinking. In the case of Parallax, during early lockdown days of the pandemic, looking out my apartment window every day over a few months, I saw fewer and fewer US Mail trucks, and more and more from Amazon specifically. I realized this was indicative of a number of things, but among them, a sort of abdicating of what used to be considered governmental services and responsibilities to corporations. I began to extrapolate a potential outcome for what might happen if governmental regulations were to be completely removed from that system. What if there are no "laws" protecting society at all, and the corporation you work for simply makes up their own that you are forced to follow?

We also sort of extrapolated on the concepts of efficiency and profit without limitation. In a world where corporations are trying to colonize distant planets instead of governments, we figured the concept of terraforming - making an inhospitable planet more earthlike over centuries - would feel tremendously unprofitable in the short-term. So instead, a pharmaceutical corporation, for example, might be more likely to gene-splice their citizens to match the environments of the planets they discover. And if that opened up a planet for colonization to that corporation, other corporations would follow suit. So now we had a unique sci-fi universe featuring a dozen different Variants of Humanity, from aquatic humans to those sharing their brain with an AI, to those designed to survive in outer space. Suddenly our universe felt fresh and vibrant, and a cascade of storylines presented themselves.

From there, Lauren and I worked it down to a much more individual scale, so this part might be categorized more as Spontaneous and Emotional Creativity. How "normal" would this system feel to people born into it? What might an individual's day-to-day look like? What if a person's parents had been aquatically-spliced, so now those traits have been passed down genetically? And what if now, their parents are gone, and the closest corporate orphanage is located on land? How stratified would society become, and what would the qualifiers for success or failure look like? What sorts of injustices would "normal" people have been taught to look the other way on? This is just our take on a scenario that many others have previously thought of, certainly, but it informed a lot of the worldbuilding of the Parallax universe.

I'm sure this all sounds super-bleak to most people. Despite the dystopic setting, I feel the need to say the Parallax is an adventure and a mystery. It's a story of regular people fighting against the machine, rather than being slaves to it. I love books like George Orwell's 1984 that are basically devoid of hope, but I don't think I could ever write one quite that dark.

How do you imagine things that don't exist?

Wow, another question I've never been asked! I guess I don't regularly speak with enough psychologists.

I think everything that doesn't exist is some sort of recombining different aspects of other things that do exist. Some of the works now considered among the most inventive science fiction shows and movies in history are reimaginings of other things. Star Wars was extremely original, but it was also George Lucas recreating one of his favorite samurai films, Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress, in outer space. The Empire draws heavily from the Third Reich, and so forth. But he combined all of these things in an intensely original way.

Nobody has ever been to another planet, but the concept of living on one has existed almost as long as we've known other planets existed. "What would happen if and when we do colonize another world?" might play out a little bit differently for everybody who imagines that story. So my brain just drifts to the story I most want to tell at that moment, and that story might change from day to day depending on my mood or which of many branching paths I choose to take that hypothetical story. A few of those stories might make for a fun project one day. They go into my spreadsheet that I call the Idea Bank. The ones that don't, my brain just ignores.

Imagining things that don't exist is just what creativity is, right? You put two Lego bricks together in one of countless different possible ways, and you just keep doing that until you have something that kind of looks like a spaceship. Given an infinite number of Inspiration Bricks and no other parameters, very rarely will two people wind up with exactly the same spaceship. Thousands of people have built their own Dungeons & Dragons campaigns, which are all basically Lord of the Rings with a few creative changes. But every group that sits down to play in that world winds up creating a totally different story.

For me, anxiety probably drives it too. Seeing endless Amazon trucks outside my pandemic window drove my brain to wonder "What if Amazon just owned every single thing?" I probably write stories in part so I can create my own slightly happier endings to things, instead of just witnessing a laundry list of problems in the real world I can't particularly solve.

What challenges did you encounter while writing?

With any writing, especially a mystery like Parallax, there is danger that comes with knowing your story too well, and then trying to remember what story points your readers may have when. So seeding the mystery without over-watering it is always a fun puzzle for my brain. You don't want readers way ahead of you, and you don't want them hopelessly lost.

In writing science fiction, there is also the complication of an unknown world. Most fiction has to balance establishing characters and building the plot in early chapters. With sci-fi, fantasy, and their sub-genres, you also have to establish the world, and often rules like science or magic, so everything that happens throughout the book feels properly foreshadowed and earned rather than some sort of Deus Ex Machina. So this is a balancing act. Some sci-fi authors are scientists as well, or do lots of scientific research before writing, so their book becomes 75% world. When everything comes together well, this enhances the story, and sometimes it takes space on the page that would otherwise be used to enhance the story or define a compelling lead character.

Character was very important to us, so we had to make sure our readers absorbed the world in a compelling way through the voice and thoughts of our protagonists without too much exposition. We didn't want to spend chapters describing how the faster-than-light mechanics in this story work, because the story isn't about that.

We also have a lot of characters, so there are a good number of plot points that are moving forward at any given time, making pacing another challenge. We wanted every character's voice to feel different, but for all of them to be fun protagonists with which to share a headspace, so it's a lot more work we made for ourselves than if we had just written with a single protagonist in mind.

Certainly the largest challenge for me in writing a book (or a TV show or a film) is figuring out the business side of the industry. Like any art, making the art is the fun part. Ensuring people see it or want to buy it is the part that becomes difficult a lot of the time. But that's not particularly related to the writing process itself, so I'll save those for another interview.

I always used to 'complain' that script writers did not have much idea about what humans are really liked. I was an early and committed Star Trek fan and I used to 'joke' that all the writers were certainly in in Jungian analysis. I see an incredible evolution in plots and character development with mixtures of plot lines, details of human inner and relational experience, etc., that is now much as Matt has described in your conversation. Helpful for me. I don't write scripts but I do write regular Field Notes on my website, and I am always looking to improve my writing. This will definitely be helpful for me.

thank you,

Avraham Cohen