Rationality, Bias, Politics, and AI

I had one of the richest and most important conversations ever with an intellectual hero of mine-- Keith Stanovich.

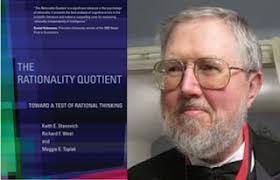

Keith Stanovich is a legend in cognitive science. When I was a graduate student I was captivated by his book The Robot’s Rebellion, and it had a major influence on my dual-process theory of human intelligence. I am very grateful he spent so much time answering my questions I and hope they have a lot of value for you too. This is a long interview, but we do cover so many topics that are of relevance in the world today. Enjoy!

Q: How did you get interested in psychology? What was your earliest research about?

I started out as a physics major, continuing in it as far as a course in quantum mechanics. I was enticed into psychology, believe it or not, by serving as a paid subject in psychology experiments to make money! I realized that psychology could be a science and ended up changing my major.

My earliest research, as a graduate student at the University of Michigan (1973-1977), focused on (rather boring) reaction-time studies of information processing (a very hot topic at the time). Things got more interesting when I met another graduate student, Richard West, and we pursued a joint interest in the information processing components of the act of reading and also the development of reading. That lead to a 20+ year collaboration and some very meaningful publications on the cognitive science of reading and reading development. In the late-1980s/early-1990s we reoriented and focused more on the second of the interests that we shared which was the psychology of reasoning and rationality. It’s that work that encompasses most of your questions.

Q: Your 2005 book The Robot’s Rebellion: Finding Meaning in the Age of Darwin influenced me greatly when I was working on my dual-process theory of human intelligence in grad school. It’s a truly profound book. Has your thinking changed much since the publication of this book?

I would say that the major conclusions and the big questions that I attempted to ask in that book have stood the test of time pretty well. The book is a synthesis of several fast-moving areas—evolutionary psychology, dual-process theory, naturalistic epistemology, memetics, the psychology of individual differences, metacognition—that is true. And it is also true that those areas of science and philosophy have developed a lot in 20 years (I’ll discuss dual-process theory in the context of another of your questions below). But none of the main arguments and philosophical questions raised by the book are changed by specific developments within each of the areas synthesized. I still think that the issues raised about what is autonomy for a human being who is colonized by two self-interested replicators (genes and memes) is still a question that is informed by the cognitive psychology discussed within the book, and still a question that is pertinent for cognitive scientists. Steve Stewart-Williams’ book The Ape That Understood the Universe: How the Mind and Culture Evolve is a more recent volume that explores similar themes.

I think that the analysis of goal conflict between personal and subpersonal entities in The Robots Rebellion is still relevant in discussions of the meaning and purpose of human life. And I still believe that the sketch of how human cognitive structure interacts with this goal conflict can still be used as a point of departure for more nuanced discussions. Your genes and the memes you have acquired pursue some personal goals of their own from their residence in System 1. To make sure you are pursuing your own goals at the personal level (at the level of the vehicle in the Dawkins terminology) you must utilize the unique capabilities of System 2, most notably you must utilize the decoupling capability of system to (what I later called the reflective mind) to create goals that are secondary representations (not actually instantiated goals of the moment) and engage in hypothetical reasoning to critique one’s own goal structure. The discussion in The Robot’s Rebellion about conflicts among first-order, second-order, and higher orders of goals is, I believe, still a useful tool in thinking about one’s own personal autonomy.

More generally, I think the distinction between replicator and vehicle and how this distinction interacts with human psychology–whatever one’s specific model of human cognition happens to be– remains of profound importance in reflecting about the meaning of life.

Q: What is the latest state of the field on dual-process theory? In grad school I remember there was this heated debate about whether to call it “System 1/System 2” or “Type 1 processes/Type 2 processes”. It was such a nerdy debate that the general public probably doesn’t care about. But where are we at with that debate? What do you see as the essential distinction between conscious System 1 processes and nonconscious System 2 processes?

You are totally correct, Scott, that it was an extremely nerdy debate and became even more nerdy after you left grad school! I’ll answer your last question first, about the essential distinction.

The defining feature of System 1 processing is its autonomy—the execution of System 1 processes is mandatory when their triggering stimuli are encountered, and they are not dependent on input from high-level control systems. Autonomous processes have other correlated features—their execution tends to be rapid, they do not put a heavy load on central processing capacity, they tend to be associative—but these other correlated features are not defining. Into the category of autonomous processes would go some processes of emotional regulation; the encapsulated modules for solving specific adaptive problems that have been posited by evolutionary psychologists; processes of implicit learning; and the automatic firing of overlearned associations.

In The Robot’s Rebellion I termed System 1 The Autonomous Set of Systems (TASS)—in order to stress that this type of processing does not arise from a singular system. The many kinds of System 1 processes have in common the property of autonomy, but otherwise, their neurophysiology and etiology might be considerably different. System 1 processing encompasses processes of unconscious implicit learning and conditioning but also many rules, stimulus discriminations, and decision-making principles that have been practiced to automaticity (so-called mindware that I will discuss below).

System 2 processing is relatively slow and computationally expensive, but these are not defining features, they are correlates. System 2’s defining feature is that it carries out cognitive decoupling. The ability to decouple representations is the foundation of hypothetical thinking and mental simulation.

In a much-cited article that is a couple of decades old, Alan Leslie modeled pretense by positing a so-called secondary representation that was a copy of the primary representation but that was decoupled from the world so that it could be manipulated—that is, be a mechanism for simulation. For Leslie, the decoupled secondary representation is necessary in order to avoid representational abuse—the possibility of confusing our simulations with our primary representations of the world as it actually is.

Thus, decoupled representations of actions about to be taken become representations of potential actions, but the latter must not infect the former while the mental simulation is being carried out. Nonetheless, dealing with secondary representations—keeping them decoupled—is costly in terms of cognitive capacity. Evolution has guaranteed the high cost of decoupling for a very good reason. As we were becoming the first creatures to rely strongly on cognitive simulation, it was especially important that we not become “unhooked” from the world too much of the time. Thus, dealing with primary representations of the world always has a special salience that may feel aversive to overcome. Nevertheless, decoupling operations must be continually in force during any ongoing simulations, and I have conjectured that the raw ability to sustain such mental simulations while keeping the relevant representations decoupled is the key aspect of the brain’s computational power that is being assessed by measures of fluid intelligence.

In short, when we reason hypothetically, we create temporary models of the world and test out actions (or alternative causes) in that simulated world. In order to reason hypothetically we must be able to prevent our representations of the real world from becoming confused with representations of imaginary situations. The so-called cognitive decoupling operations that make this possible are the central defining feature of System 2 processing.

Q: Where are we at with the dual-process debate?

This debate has actually seemed more contentious than it really is because many of “disputes” are really pseudo-disputes. This literature has followed a particular developmental sequence that is often seen in psychology. Initial investigators flesh out a new idea/methodology/finding in a crude way and write a seminal paper on the new idea. These investigators themselves, and others they have inspired, then go on to refine the topic in subsequent papers. But often, well after the period of theoretical refinement has set in, papers begin appearing in the literature attacking the original crude model that was initially presented in the seminal paper. Of course, some of this is understandable given the normal publication lags in our science. Often, however, the phenomenon continues long after the time that it could be chalked up to publication lag. Long after the forefront of the field has moved on to more refined models, the original crude (and thus easier to attack) version of the theory remains the subject of critique (as a strawman).

The dual-process literature has suffered a bit from just this strategy. Many dual-process notions sprung up in the 1970s. Jonathan Evans’ heuristic-analytic model kept the idea alive in the 1980s. However, it was in the 1990s that these theories really began to proliferate across a diverse set of specialty areas in psychology and other disciplines, including cognitive psychology, social psychology, clinical psychology, neuropsychology, naturalistic philosophy, economics, and decision science. Many of these theories did not cross reference each other though; and neither did most of them refer to the foundational work of the 1970s.

In order to bring some coherence and integration to this literature, researchers in the late-1990s such as Steve Sloman, Jonathan Evans, and myself, brought together some of the pairs of properties that had been posited in the literature to indicate the differences between the two processes. Many of us published lists of the complementary properties of the two processes. The purpose of publishing these tables in the 1990s was simply to bring together the many properties that had been assigned to the two processes in the proliferation of dual-process theories over the years. The list was not intended as a strict theoretical statement of necessary and defining features. We were merely searching for “family resemblances” among the various theories. These lists were descriptive of terms in the literature—they were never intended as full-blown theory of necessarily co-occurring properties.

The main misuse of such tables is to treat them as strong statements about necessary co-occurring features—and then to attack dual-process theories when so-called “misalignment” was found (the properties in the tables where not completely co-occurring). But dual-process theory does not stand or fall on the full set of properties in tables like this necessarily co-occurring. They were merely precursors to the investigations that later zeroed in on autonomy and decoupling as being the defining features.

A positive development in dual-process theories over the last decade or so has been a more thorough understanding of how stored knowledge (mindware) interacts with processing components of dual-process theory. For example, dual-process theories have often relied on heuristics and biases tasks that require the override of a System 1 response by System 2 when they are in conflict. Detection of the conflict and override are the processing components of successful performance. It was always the case (but often ignored in the literature) that successful performance on heuristics and biases tasks is also dependent on stored knowledge of various types.

Recognizing the importance of mindware can help prevent some common mistaken inferences when investigators employ dual-process theory. One mistaken inference is the idea that all errors must be fast (the result of miserly reliance on System 1) and that all correct responses must be slow (the result of a computationally taxing override process from System 2). But such an inference ignores the fact that within System 1 can reside normative rules and rational strategies that have been practiced to automaticity and that can automatically compete with (and often immediately defeat) any alternative nonnormative response. This idea is not new. The category of autonomous processing in cognitive science has long included the automatic triggering of overlearned rules (going back to the work of Posner & Snyder and Shiffrin & Schneider in the 1970s).

I drew attention to the mindware component of dual-process theory in a theoretical piece in Thinking & Reasoning in 2018, but Wim De Neys has a comprehensive research program on the issue and has integrated the insights of many different investigators on the importance of mindware in his recent target article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Q: One criticism I have had of your work is that you tend to treat System 1 nonconscious processes as mostly irrational, elevating conscious System 2 processes above the others in importance. I found in my own research that individual differences in implicit learning, for instance, predicts creativity, openness to experience and artistic creativity. Have your thoughts about the value of System 1 processes changed at all over the years?

I think one reason you have that impression is the we relied so much on the heuristics and biases literature and heuristics and biases framework. It is deliberately over-ripe with tasks where an incorrect response generated by System 1 must be overridden by System 2 if the problem is to be answered correctly.

But the literature was originally biased in this direction for a good reason. In previous papers I have framed the issue in terms of benign versus hostile environments. A benign environment contains useful cues that can be used by various heuristics. Additionally, for an environment to be classified as benign, it also must contain no other individuals who will adjust their behavior to exploit those relying only on heuristics. In contrast, a hostile environment is one in which the use of heuristics leads the subject astray or one that contains other agents who arrange the cues for their own advantage.

For example, heuristics and biases problems are more hostile than typical IQ test problems in that the latter often do not contain enticing lures toward an incorrect response. Neither is the construal of an IQ test item left up to the subject. Instead, the instructions to an IQ test item attempt to remove ambiguity in a way that is not true of a heuristics and biases problem (the Linda conjunction problem would be a prime case in point). IQ tests measure the computational capacity of what I call the algorithmic mind.

But I want to stop here and point out that nothing I have said contradicts the point you are alluding to, and that I want to acknowledge here: that is, on a token basis, the vast majority of outputs from System 1 are highly rational. We pointed out this fact in earlier papers, but needed to emphasize it further, and we did it is a paper in Perspectives in Psychological science that I co-authored with Jonathan Evans.

Recall earlier that in various publications I have labeled System 1 The Autonomous Set of Systems (TASS) to emphasize that there are many different systems within it and the majority of them are highly functional for the organism and that they produce a plethora of rational outputs. For example, I have emphasized that the category of autonomous processes would include: processes of emotional regulation; the encapsulated modules for solving specific adaptive problems that have been posited by evolutionary psychologists; processes of implicit learning; and the automatic firing of overlearned associations. All of these are highly functional systems producing rational responses in the vast majority of individual cases. This is what I mean when I say that, on a token basis, System 1 is highly rational. But there certain types of situations (where the systems are in conflict, as described above) that are important in real life that necessitate a System 2 override. It was never intended (by me or by Kahneman & Tversky) that emphasizing this point denigrates the contributions from System 1. The field has taken a couple of decades to dig itself out from this interpretation.

Q: In your research, which particular forms of rational thinking have you found to be least strongly correlated with IQ? What about most strongly correlated with IQ?

You are correct to ask about the forms or components of rational thinking rather than rational thinking itself because the latter is a multifarious concept involving many different subcomponents. In our Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking (CART), described in our book The Rationality Quotient, we measured 20 different components of rationality and four different thinking dispositions related to rational thinking. Your question implies, correctly, that different components of rational thinking have different relationships with intelligence/cognitive ability. I’ll describe some of the components that span the continuum of this relationship.

There are fairly strong correlations, in the range of .45-.55 between cognitive ability and several components of rational thinking in the CART such as probabilistic reasoning, scientific reasoning, avoiding belief bias in syllogistic reasoning, and probabilistic numeracy. Moderate correlations in the range of.25-.35 are found for rational thinking components such as avoiding framing effects in decision-making, avoiding anchoring biases, avoiding overconfidence, and evaluating informal arguments. We find fairly low correlations between cognitive ability and preference anomalies in decision-making and temporal discounting. So there are a range of relationships.

Q: Another criticism I have had is that in your methodology you rarely conduct a latent factor analysis of general intelligence and your rationality measures. When I do that, I find a very strong correlation between the general factor of intelligence and a general factor of rationality. Maybe I’ve missed it, but have you ever conducted a really large latent factor analysis of both constructs to see the correlation between both latent constructs?

So we’ll have to be careful in answering this question to differentiate between a latent analysis of general intelligence and specific rationality measures and a latent analysis of general intelligence and “a general factor of rationality”. Regarding the former, there has not been a lot of work but there has been some–a little bit in our own lab and some by other labs such as the Burgoyne/Engle lab and the Erceg lab. Regarding the components, these analysis will give you outcomes like I have discussed in the previous paragraph. So in terms of subcomponents such as probabilistic reasoning and scientific reasoning, the raw correlations we published in the book, .45-.55, are pretty much recapitulated in the latent analyses we have conducted on these subcomponents. The latent correlation between cognitive ability and a small number of probabilistic reasoning tasks hovers in the range of .50-.60 in analyses that we have done and in those by the Burgoyne/Engle lab.

But moving to the second question, “a general factor of rationality,” we have not done such analyses because we do not believe that there is a latent construct called rationality. Specifically, there is no reason to expect a g-concept of fluid-g concept analogous to the fluid-g concept in intelligence research. Subcomponents of rationality will simply not cluster in the manner of say, CHC theory, because their underlying mental requirements are too diverse and too complex. We would not expect our rationality subscales to hang together in a particular predetermined structure because not only are there different types of mindware involved in each but also, for many of the subtests, there are different types of miserliness involved (default to System 1 processing; serial associative cognition; override failure—all described in The Rationality Quotient book).

If rationality as a concept were to be modelled, it would be as a formative concept rather than a reflective concept. Latent modelling that defaults to the notion that it is a standard reflective concept (yielding a g, or something of the sort) will yield misleading results. In the book, we discuss the difference between formative and reflective models of constructs, relying heavily on the classic early work of Bollen and Lennox. They discuss how, in reflective models, the direction of causality is from construct to measures, but in formative measurement models it is from measures to construct. In the case of formative measurement models, indicators are defining characteristics of constructs and changes in indicators cause changes in the construct. In the contrasting case of reflective models, indicators are manifestations of the construct and changes in an indicator do not cause changes in the construct.

Indicators in formative models do not necessarily share a common theme, but they do in the case of reflective models. In the latter, individual indicators are interchangeable and replaceable; in the former they are not. A change in the level of an indicator in a formative model is not necessarily expected to be accompanied by changes in the levels of other indicators. Whereas, in a reflective model, a change in one indicator should be accompanied by changes in others, because the change in one reflects some kind of change in the latent construct.

Bollen and Lennox, and other authors we cite, discuss several examples of formative concepts. For example, the concept of life stress has been defined by job loss, divorce, medical problems, and the recency of a death in the family. Such a concept is formative in that the measured variables define the construct rather than the measured variables being manifestations of a unitary latent variable. A change in one indicator of the formative construct life stress—such as a death in the family—would not lead to the expectation that there would be commensurate changes in other indicators (such as divorce) as would be the case with a reflective construct. Several examples of formative constructs from the economics literature include composite formative variables of economic welfare, human development, and quality of life. Constructs such as these have the same logic as other formative constructs in that a change in one indicator does not necessarily lead to the expectation of the change in another. The causal direction is from indicator to construct rather than from construct to indicator (as is the case with reflective models).

A formative measurement model is more appropriate for a multidimensional construct like rational thinking. Any global notion of rational thinking is best viewed as a formative one composed of very disparate elements that we would not necessarily expect to cohere because they are not the result of some unified latent concept of rational thought. Indicators in formative models do not necessarily share a common theme, but they do in the case of reflective models. In the latter, individual indicators are interchangeable and replaceable; in the former they are not (thus, we would not expect a formative construct to have extremely high internal reliability).

Any global notion of rationality (such as one suggested by the calculation of a composite score) would have to be understood in the same manner as these other formative concepts in other disciplines—where the causal direction is from indicator to construct rather than from construct to indicator. Rational thinking is not a unified core ability defined by many different interchangeable indicators. It is disparate set of skills across broad domains such as those tapped by the CART. Statistically, these points cash out in the warning, conceptually, that you cannot just throw all these rational thinking subcomponents into the “washing machine” of latent factor analysis, assume that you are dealing with a reflective concept, and get something that makes sense. You are correct that this is a warning that we have been issuing much too late in the day, and some of our earlier discussions might have led people astray. We even constructed a composite score once, and it is one my greatest regrets, because it mistakenly suggested a reflective latent concept analogous to g.

Q: What do you think is the single most important cognitive bias facing humans today?

A few years back I reviewed Steven Pinker’s superb book Rationality, and noted the uncomfortable way that the book ends. In the book, Pinker chronicles how, by rational means, we have accomplished any number of supreme achievements such as curing illness, decoding the genome, and uncovering the most minute constituents of matter. Yet, all of this exists alongside surveys showing that 41% of the population believes in extrasensory perception, 32% in ghosts and spirits, and 25% in astrology—just a few of the pseudoscientific beliefs that Pinker lists. These facts highlight what Pinker calls the rationality paradox: “How, then, can we understand this thing called rationality which would appear to be the birthright of our species yet is so frequently and flagrantly flouted?”

Pinker goes on to honestly—but shockingly—admit that the solution to this “pandemic of poppycock” is not to be found in correcting the many thinking biases that are covered in his book. Many of the biases covered in his book arise from people lacking the specialized knowledge (mindware) that is necessary to compute the response. A different class of error sometimes arises, however, because not all mindware is helpful. In fact, some mindware is the direct cause of irrational thinking. I have called this the problem of contaminated mindware. The “pandemic of poppycock” that Pinker describes at the outset of Chapter 10 comes precisely from this category of irrational thinking. And that’s bad news.

It’s bad news because we can’t remediate this kind of rational thinking through teaching. People captured by this poppycock have too much mindware—not too little. Yes, learning scientific reasoning more deeply, or learning more probabilistic reasoning skills might help a little. But Pinker agrees with my pessimism on this count, arguing that “nothing from the cognitive psychology lab could have predicted QAnon, nor are its adherents likely to be disabused by a tutorial in logic or probability.”

This admission uncomfortably calls to mind a quip by Scott Alexander that “of the fifty-odd biases discovered by Kahneman, Tversky, and their successors, forty-nine are cute quirks, and one is destroying civilization. This last one is confirmation bias—our tendency to interpret evidence as confirming our pre-existing beliefs instead of changing our minds.”

This quip is not literally correct, because the “other 49” are not “cute quirks” with no implications in the real world. In his final chapter, Pinker describes and cites research showing that these biases have been linked to real-world outcomes in the financial, occupational, health, and legal domains. They are not just cute quirks. Nevertheless, the joke hits home, and that’s why I wrote a book on the one bias that is “destroying civilization.”—my book on myside bias, The Bias That Divides Us.

In the penultimate chapter of his book titled “What’s Wrong With People” Pinker focuses on motivated reasoning, myside bias, and contaminated mindware. Having studied these areas myself, it was no surprise to me that this chapter was not an encouraging one from the standpoint of individual remediation. Most cognitive biases in the literature have moderate correlations with intelligence. This provides some ground for optimism because, even for people without high cognitive ability, it may be possible to teach them the thinking propensities and stored mindware that makes the highly intelligent more apt to avoid the bias. This is not the case with the “one that’s destroying civilization.” The tendency to display myside bias is totally uncorrelated with intelligence, as I describe in The Bias That Divides Us.

Myside bias also has little domain generality: a person showing high myside bias in one domain is not necessarily likely to show it in another. On the other hand, specific beliefs differ greatly in the amount of myside bias they provoke. Thus, myside bias is best understood by looking at the nature of beliefs rather than the generic psychological characteristics of people. A different type of theory is needed to explain individual differences in myside bias. Memetic theory becomes of interest here, because memes differ in how strongly they are structured to repel contradictory ideas. Even more important is the fundamental memetic insight itself: that a belief may spread without necessarily being true or helping the human being who holds the belief in any way. For our evolved brains, such beliefs represent another aspect of a hostile world.

Properties of memes such as non-falsifiability have obvious relevance here, as do consistency considerations that loom large in many of the rational strictures that Pinker discusses. Memes that have not passed any reflective tests (falsifiability, consistency, etc.) are more likely to be those memes that are serving only their own interests—that is, ideas that we believe only because they have properties that allow them to easily acquire hosts.

People need to be more skeptical of the memes that they have acquired. Utilizing some of the thinking dispositions like actively open-minded thinking that Pinker discusses and that my research group has researched extensively. We need to learn to treat our beliefs less like possessions and more like contingent hypotheses. People also need to be particularly skeptical of the memes that were acquired in their early lives—those that were passed on by parents, relatives, and their peers. It is likely that these memes have not been subjected to selective tests because they were acquired during a developmental period when their host lacked reflective capacities.

All of this is heavy lifting at the individual level, however. And it actually relates to another of your questions:

Q: What can we do to reduce this bias?

The remedy for our society-wide crisis of political polarization driven by myside bias won’t be any quick fix at the individual level. Ultimately, we all need to rely on the “institutions of rationality”—cultural institutions that enforce rules that enable people to benefit from rational tools without having to learn the tools themselves. But here we encounter a glitch.

These are precisely the institutions that have lost their status as neutral adjudicators of truth claims in recent years (the media, universities, scientific organizations, government bureaucracies). The answer cannot be to tell the populace to turn more strongly to the same institutions that have been failing us. You can’t do that unless you change the institutions themselves. Pinker describes how “on several occasions correspondents have asked me why they should trust the scientific consensus on climate change, since it comes out of institutions that brook no dissent.” I concur with Pinker here. The public is coming to know that the universities have approved positions on certain topics, and thus the public is quite rationally reducing its confidence in research that comes out of universities.

Take science and the universities, for example, the institutions I know best. In my book, I discussed the unique feature of science that allows it to overcome the myside bias of individual scientists. In that discussion, I emphasized that science works so well not because scientists themselves are uniquely virtuous (that they are completely objective or that they are never biased), but because scientists are immersed in a system of checks and balances where other scientists with differing biases are there to critique and correct. The bias of investigator A might not be shared by investigator B who will then look at A's results with a skeptical eye. Likewise, when investigator B presents a result, investigator A will tend to be critical and look at it with a skeptical eye.

However, it should be obvious what can ruin this scientific process of error detection and cross-checking. What ruins it is when all of the investigators share exactly the same bias! Then, the social process of error checking and correction cannot work as I described it in the book. Unfortunately, many social sciences, and many fields in the university, are in just such a situation with respect to political ideology. The pool of investigators is politically homogeneous, and thus we cannot rest assured that there is enough variability in social science or in the university to cancel out myside bias in the manner that yields an overall objective conclusion on politically charged topics.

With the advent of DEI statements in faculty hiring and the resultant disciplines that have become ideological monocultures, there is little hope that the universities will have a more ideological heterodox faculty in the future. Instead, current procedures will insure that faculties will become more and more ideologically uniform, and thus more prone to conclusions freighted with a heavy myside bias.

These institutions simply have to reform themselves in order to “let the other half of the public in,” as I have phrased it. There is one half of America who thinks differently about the pressing issues of the day than does the contemporary social science professoriate. If we try to adjudicate empirical findings relevant to these issues, our conclusions will not be believable to the broad public unless we engage in true adversarial collaboration with our ideological opponents.

There seems to be a kind of doubling down in academia at the moment, an insistence that the ideological monoculture is not a bug, but is instead a feature; an insistence that if you question the potentially biased construction of our measures of knowledge and knowledge acquisition, then you have a secondary deficiency because you “deny trusted knowledge sources” or “question the conclusions of experts.” Institutions, administrators, and faculty seem unconcerned about the public’s plummeting trust in universities.

Most Americans though, see the monoculture as a bug. If academia really wanted to fix the bug, it would be turning strongly to the mechanism I mentioned above—adversarial collaboration. Conclusions based on adversarial collaborations can be fairly presented to consumers of scientific information as true consensus conclusions and not outcomes determined by one side’s success in shutting the other out. A major obstacle to expanding adversarial collaboration, of course, is that ideological cleansing of many social science departments is now so complete that we won’t have enough of a critical mass of conservative scholars to function in the needed adversarial collaborations.

Other institutions for adjudicating knowledge claims in our society, just like university social science, have been too cavalier in their dismissal of the need for adversarial collaboration. For example, fact checking often fails in the political domain for this reason. The slipups that occur on fact checkers always seem to favor the ideological proclivities of the liberal media outlets that are the sponsors of the fact checking operations. Fact checking organizations seem oblivious to an implication from research on myside bias—that a primary source of bias is the selection of items to fact check in the first place. More problematic than inaccuracies in the fact checks themselves is the automatic myside bias that will trigger choosing one proposition over another for checking amongst a population of thousands. Fact checkers have become just another player in the unhinged partisan cacophony of our politics. Academics use fact checking sites to double down—if you don’t believe them, they say, you are not “following the science.” But many of the leading organizations are populated by progressive academics in universities, others are run by liberal newspapers, and some are connected with Democratic donors. You cannot possibly expect such entities to win respect among the general population when they have such ideological connections and when they do not fully instantiate inclusive adversarial collaboration.

Q: Why do you think America is so divided politically and what can we do about it?

I participated, a couple of years ago, in a special journal issue of the Journal of Intelligence on the role of intelligence and other thinking skills in solving contemporary world problems such as climate change, poverty, pollution, violence, terrorism, a divided society, and income disparities (among others). I argued that the many issues on this list may be in very different categories. Some of them, like poverty and violence, may be solvable by more rational policy changes. These problems actually have been ameliorated greatly over time, as Pinker has shown in several of his books.

However, other issues on this list—such as climate change, pollution, terrorism, income disparities, and most definitely the problem of a divided and polarized society—may be of a different type than poverty and violence. Perhaps, in some of these cases, what we are looking at are not problems that we would expect to be solved by greater intelligence, rationality, or knowledge, but rather problems that arise due to conflicting values in a society with diverse worldviews. For example, pollution reduction and curbing global warming often require measures which have as a side effect restrained economic growth. The taxes and regulatory restraints necessary to markedly reduce pollution and global warming often fall disproportionately on the poor. For example, raising the cost of operating an automobile through the use of congestion zones, raised parking costs, and increased vehicle and gas taxes restrains the driving of poorer people more than that of the affluent. Likewise, there is no way to minimize global warming and maximize economic output (and hence, jobs and prosperity) at the same time. People differ on where they put their “parameter settings” for trading off environmental protection versus economic growth. Differing parameter settings on issues such as this are not necessarily due to lack of knowledge. They are the result of differing values, or differing worldviews.

Problems such as climate change and pollution control involve tradeoffs, and it is not surprising that the differing values that people hold may result in a societal compromise that pleases neither of the groups on the extremes. It is the height of myside bias to think that if everyone were more intelligent, or more rational, or wiser, then they would put the societal settings exactly where you put your own settings now. There is in fact empirical evidence showing that more knowledge or intelligence or reflectiveness does not resolve zero-sum value disagreements such as these.

The case of income disparities as a social problem provides another illustration of the trade-offs involved in some problem solutions. Political disputes about income disparity are value conflicts—not conflicts between the knowledgeable and unknowledgeable. There is no optimal level of the Gini index for a given country (the Gini index is the most commonly used measure of inequality in economics—where a higher Gini index indicates more inequality). Talking about “the problem” of income inequality seems to be somewhat of a misnomer when no one knows the optimal Gini coefficient for a country.

Take, for example, the fact that although income inequality has been increasing in the past couple of decades in most industrialized, first-world countries, worldwide indices of income inequality have been decreasing during the same period. These two trends may well be related—through the effects of trade and immigration. The very same mechanisms that are supporting decreases in world inequality may well be supporting increases in inequality within the United States. Which of the two inequality measures (world or US) we want to focus on is a value judgment.

Likewise, consider the following facts about income equality in the United States in the last 30 years: the top 10% of the population in income and wealth has pulled away from the middle of the population more than the middle has detached from the poor. So when trying to reduce overall inequality—in the manner that would affect an omnibus statistic like the Gini index—we need to make a value judgment about which of these gaps we want to concentrate on more. The obvious answer here for any equality advocate—that we want to work on both gaps—simply will not do. Some of the policies focused on closing one of these gaps may well operate to increase the other gap. When we say we are against inequality we really have to make a value judgment about which of these gaps mean more to us.

In short, income inequality is a “problem” that does not have a univariate solution. Disagreements about it arise from value differences—not because one segment of the population lacks knowledge that the other possesses.

Another social issue on the list above—a divided society—is a quintessential illustration of the kind of “problem” that is going to be most opaque to solution via an appeal to mental faculties such as intelligence, rationality, knowledge, or wisdom. Political divisiveness in society is largely due to value conflict. Thinking that political divisiveness can be resolved by increasing any valued cognitive characteristic would seem to be the epitome of a myside bias blind spot. To put it a bit more colloquially, for a conservative to think that if we were all highly intelligent, highly rational, extremely knowledgeable, and very wise, all divisiveness would disappear because we would then all be Republicans would seem to be the height of myside thinking. And likewise, for a liberal to think that if we were all highly intelligent, highly rational, extremely knowledgeable, and very wise that all divisiveness would disappear because we would all then be Democrats would seem, again, to epitomize the height of myside thinking.

As cognitive elites, we can tame our myside bias by realizing that, in many cases, our thinking that certain facts (that, due to cherry-picking, we just happen to know) are shockingly unknown by our political opponents is really just a self-serving argument about knowledge that is used to mask the fact that the issue we are talking about is a value conflict. Our focus on the ignorance of our opponents is simply a ruse to cover up our conviction that our own value weightings should prevail—not that the issue is one that will be resolved by more knowledge.

Cognitive elites are mistaken in many of these cases because they tend to overestimate the extent to which political disputes are about differential possession of factual knowledge and underestimate how much they are actually based on a clash of honestly held values. We have undergone decades of progress in which we have probably already solved most societal problems that have solely empirically-based solutions. All of the non-zero-sum problems where we can easily find a Pareto improvement (where some people can gain from a policy without anyone else in society losing) likely tend to be problems that have already been ameliorated. The contentious issues that we are left with are those that are particularly refractory to solution via the use of knowledge that we already have. If an issue is squarely in the domain of politics, it is probably not “just a matter of facts.”

My discussion here has borrowed from a section in my myside book that attempted to provide remedies for the myside-driven political polarization that threatens our society. My responses to you here are on the long side already, so I will just whet the reader’s appetite with some of the subtitles in the book that also focus on ameliorating the negative effects of myside bias:

Treat Your Beliefs Less Like Possessions by Realizing:

“You Didn’t Think Your Way to That”

Be Aware that Myside Bias Flourishes in Environments of Ambiguity and Complexity

Be Aware That Partisan Tribalism Is Making You More Mysided Than Political Issues Are

Oppose Identity Politics Because It Magnifies Myside Bias

Recognize That, Within Yourself, You Have Conflicting Values

Recognize That, in the Realm of Ideas, Myside Bias Causes an Obesity Epidemic of the Mind

Q: Does the emergence of AI as an existential threat cause you concern? Will humans be able to rebel against the robots someday? (See what I did there? )

That’s a clever question, Scott, and in fact your question plays a role in one recent paper on the existential threat of AI that actually used the arguments in The Robot’s Rebellion to develop a frightening implication of AI. The paper is, by the way:

Tubert, A., & Tiehen, J. (2024). Existentialist risk and value misalignment. Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-024-02142-6

The article draws on my discussion of the second and third-order evaluation of goals/desires (strong evaluation in the terms of Charles Taylor) and its role as a unique feature of human cognition. Tubert and Tiehen (2024) follow through on the implication that if human-like intelligence requires strong evaluation, then true human-like AI will necessarily carry the risk of so-called “existential choices”—choices that transform who we are as persons, including transforming what we most deeply value or desire. It is a capacity for a kind of value misalignment, in that the values held prior to making such choices can be significantly different from (and misaligned with) the values held after making them. True human AI will necessarily entail value misalignment—an inference that follows directly from the arguments in The Robot’s Rebellion.

Q: What else is on your mind these days? What are you working on these days that most excites you?

My colleague Maggie Toplak (York University, Canada) and I are working on several papers that attempt to reconceptualize how conspiracy belief is studied in psychology. We are attempting to merge perspectives from political science and philosophy with work in psychology. The latter discipline has tended to pathologize conspiracy belief by focusing its scales on the most outlandish of conspiracy beliefs. It also tends to downplay the fact that because conspiracies actually do occur with regularity in the world, the optimal (i.e, most rational, if you will) amount of conspiratorial ideation that one should show is not zero. Work in political science and philosophy has been more prone than that in psychology to recognize that the conspiratorial thinking disposition has some functionality.

We have also worked on overhauling the terminology in this area. One problem is the continued use of the term “conspiracy theory” in scientific work. The term has become irredeemably contaminated by trends in popular usage—which now point to the term as meaning a conspiracy belief that is both falseand irrational. Journalist Jesse Walker has demonstrated how the phrase first morphed from meaning a posited conspiracy, into meaning “implausible conspiracy theory,” and finally into meaning “implausible belief whether it involves a conspiracy or not.”

The term “conspiracy theory” has also become a popular epithet in political debates where it is used as a rhetorical weapon to discredit ideas without having to make actual arguments against them. When this rhetorical move is made by the politically powerful, as is increasingly the case, the phrase “conspiracy theory” becomes little more than a weapon disproportionately wielded by those with more control of communication channels. The notorious case of the lab leak conjecture during Covid-19 being prematurely tarred as a conspiracy theory would be a case in point of such weaponization.

Even within science itself, the term has been tainted by the biased selection of conspiracy beliefs that appear in the scales used in studies. It is not uncommon to see articles in which the investigators have studied older false conspiracy beliefs and then proceed to extend the results to contemporary posited conspiracies whose truth status is still undetermined.

We are attempting to direct psychology back to a more neutral study of this domain by focusing on precursor or “upstream” psychological attitudes such as belief in hidden causal forces and political attitudes such anti-elitism. Belief in causal forces hidden from the public is probably the variable that the field of psychology should have been studying from the beginning of its investigations in this area. Instead, the field adopted an “I-know-it-when-I-see-it” attitude that licensed stimulus selection based on the intuitions of experimenters regarding what was bad thinking. Thus, this field followed psychology’s inglorious history of reaching biased conclusions and theoretical dead ends because it consistently over relies on the unrepresentative intuitions of its (ideological biased) investigators. Starting with the most preposterous of conspiracy beliefs and loading the literature with the correlates of such beliefs leads the field into premature conclusions based on an extremely biased stimulus subset.

In our earlier work oriented toward constructing the Conspiracy Beliefs subtest for the CART, we conceptualized conspiracy belief within a contaminated mindware framework. That is, we viewed the conspiracy beliefs that a person held as a subset of the defective declarative knowledge that the individual had stored, and we assumed, for scoring purposes, that the optimal amount of contaminated mindware should be zero. We now think that this approach has numerous defects.

Instead, a focus on hidden causal forces moves the focus in a dispositional direction. A focus on belief in forces hidden from the public as an attitude/disposition rather than specific and highly selected false beliefs, would also move the field from the automatic assumption that any sort of conspiratorial thinking is prima facie irrational. This will be a hard assumption for psychologists to give up, because the inherent interest in the field for some investigators is fuelled by the perception that belief in conspiracies is highly irrational. Indeed, the earliest scales measuring individual differences in conspiracy belief were constructed under the assumption that it was clearly and obviously irrational. That was certainly true during 2012-2015, when we constructed the conspiracy belief subtest of the CART.

Conspiratorial thinking becomes most disposition-like when derived from minimalist definitions of what a conspiracy belief is—for example, at least two agents coordinating or colluding, undetected by the public, toward a goal of significant public interest. Using such definitions prevents researchers from pre-determining the important correlates in advance and it does not suggest the default assumption that avoiding conspiracy belief entirely is the maximally rational response.

Our world is full of large and complex institutions (governments, corporations, the military, internet platforms, universities, mass media, foundations, international organizations, etc.). These organizations are filled with many people having many different goals—sometimes goals the conflict with the organization’s publicly professed mission. It is commonplace for these large organizations to fall short of their missions because groups of individuals within them pursue outcomes not exactly aligned with the professed organizational mission.

Even when large institutions actually do honestly and efficiently pursue their stated mission, it is often the case that they believe that public knowledge of intermediate goal states will impede their objectives. When they think this, there is pressure to make actions opaque to the public. In a world of increasing complexity and global interaction—and increasing potential conflicts among fractious and polarized interest groups—why wouldn’t you think that some of the groups were colluding and coordinating to advance a goal that remains empirically opaque to the public? In light of these facts about the structure and complexity of the modern world, it is absolutely adaptive, indeed rational, for the average citizen to have some degree of suspicion that there are hidden or undetected forces determining the changes they see in their lives.

Of course, this cautionary mental attitude will sometimes be overdone, and will lead to epistemically unwarranted beliefs of various kinds. Sometimes a highly cautionary attitude toward hidden forces will combine with other mental traits like the propensity for risky explanations (indicated in our study by a Paranormal Beliefs scale) and lead to epistemically unwarranted beliefs. But, a priori, it is hard to know when one has crossed this very ambiguous line. Government officials do indeed often work for ends that serve themselves rather than their governmental function, and this is not rare. Of course, businesses act, sometimes, to subvert the interests of their workers and the consumers of their products. Even non-profit institutions tacitly act, at times, to perpetuate the social problem that is their rationale for existence. Many individuals in institutions engage in tacit collusion to benefit their own ends rather than publicly stated institutional goals. Thus, a more balanced approach to this topic is needed and that is what we have been trying to achieve with our new research.

Keith E. Stanovich is Emeritus Professor of Applied Psychology and Human Development at the University of Toronto and former Canada Research Chair of Applied Cognitive Science. He is the author of over 200 scientific articles and nine books.

Conspiracy theories I think is a funny story. We used to believe in God. Now that we don't, we are left wondering who is pulling on the strings. 'Cause God might not be felt as much on individual level, but her influence on the societal scale is a bit harder to dismiss.*

By the way, those so-called "peak experiences" look very much like the individual experiences of God. Of course, not everyone has them (I don't). But we can explain them (and God) rationally. Or scientifically, if you will.

"God does not proclaim Himself. He is everybody's secret, but the intellect of the sage has found Him." ~Katha-Upanishad

https://open.substack.com/pub/silkfire/p/ep7-the-nature-of-god

* I mean I used to believe in democracy until I had to face the truth -- something Socrates realized from the start -- that democracy can't work as advertised. It depends on most people understanding social and economic policy and, as matter of fact, they don't. They'd vote for Hitler, then kill and die for him by millions, and then everyone would be looking at the smoldering ruins and wondering what the f*ck just happened? Not for long of course. Not until it happens again.

“How long, O Lord, must I call for help? But you do not listen! ‘Violence is everywhere!’ I cry, but you do not come to save.

Must I forever see these evil deeds? Why must I watch all this misery?

I am surrounded by people who love to argue and fight. The law has become paralyzed. The wicked far outnumber the righteous, so that justice has become perverted.” (Habakkuk 1:2-4)

The more thing change, the more they stay the same. If democratic (or otherwise) societies are not imploding, it's only because something/somebody is carefully pulling on strings, holding them together. Many feel it, of course, and suspect malice... of course.

System 1 is a raw neural network, these day also known as machine-learning AI. It is also the underwater part of the iceberg -- a neural network supercomputer that operates autonomously in our subconsciousness, learning statistical models and applying them to make inferences about our environment. It gives us things like intuition, creativity, our sense of beauty and, ultimately, it makes our choices -- we always choose what we _feel_ is the best course of actions, and that feeling is the result of the subconscious AI evaluating available options against the life-time of experience.

Ironically, it is System 2 that remains a mystery. How do we understand rationally? Although we achieve understanding through conscious effort, most people apparently lack the introspection to explain how they do it! Here is my take (and yes, this is how I do it -- it's not verbal, it's visual):

https://open.substack.com/pub/silkfire/p/ep-4-what-this-is-all-about