Rethinking the Origins of Greatness

A new review paper challenges our assumptions about how exceptional performance develops.

In each field of human endeavor, only a small number of people reach the highest echelons of performance. All around the world, gifted education programs, college admissions committees, and elite training institutions aim to select the top early performers and then seek to further accelerate their performance through intensified training within their area of talent. This may help produce young high achievers, but is it identifying potential for eventual adult greatness? A new large analysis suggests that we may have to rethink all of these assumptions about the development of adult elite performance.

Sports scientist Arne Güllich and his colleagues looked at evidence from 19 datasets including 34,839 adult international top performers in different domains— from world-class athletes to Nobel laureates in the sciences, to the world’s best chess players, to the most renowned classical musical composers. They compared this data against 66 representative studies conducted among young and sub-elite performers.

What did they find? Let’s start with their sports analysis. Their large-scale analysis examined performance data over time from more than 50,000 athletes, including 3,375 international medalists, across every sport played at the Olympic Games. In their own words:

“The findings revealed that elite youth athletes and later elite adult athletes are rarely the same individuals at both time points— that is, they are largely two discrete populations.”

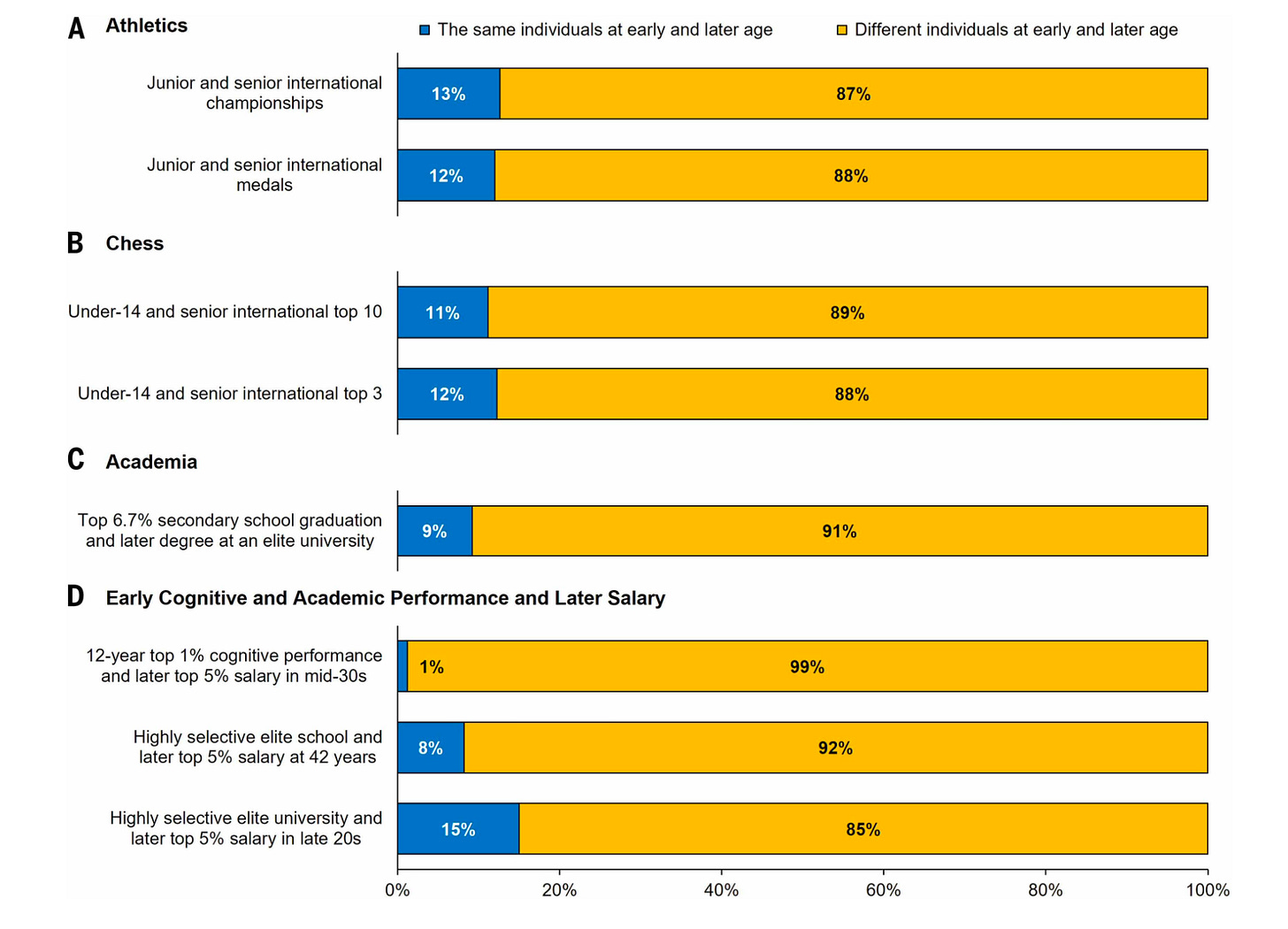

Holy cow! The vast majority— nearly 90%!— of junior and later senior international-level performers are different athletes. When examining the top performers within this already elite group, junior and senior international medalists were also nearly 90% different athletes.

Chess? Same pattern. The world’s top 10 at under-14 age and later top 10 adult chess players across time were nearly 90% different players. Academia? Same. About 90% of the top secondary and later top university students are different people across time.

As they note, it’s more difficult to look at the same metrics across other fields because there are little to no exceptional youth fighter pilots, brain surgeons, stock market traders, or world-class mathematicians. So the researchers used top cognitive and academic performance and later adult yearnings as proxies. While I find these proxies dubious, it doesn’t matter because even using these proxies of so-called “lifelong potential”, early and later exceptional performers are by and large different people. From the researchers:

“The top 1% of childhood cognitive performers and later top 5% of earners are 99% different people. The top graduates from high selective elite schools and later top 5% of earners are 92% different people; and the top graduates from highly selective elite universities and later top 5% of earners are 85% different people.”

This data is consistent with prior research in the domain of classical music that suggests that child prodigies rarely become top adult top musicians. Taken together, the analysis of this enormous dataset consistently paints the picture that most early top performers do not become top performers at peak age and most top performers at peak age were not early top performers.

Performance Trajectories of Elite Performers

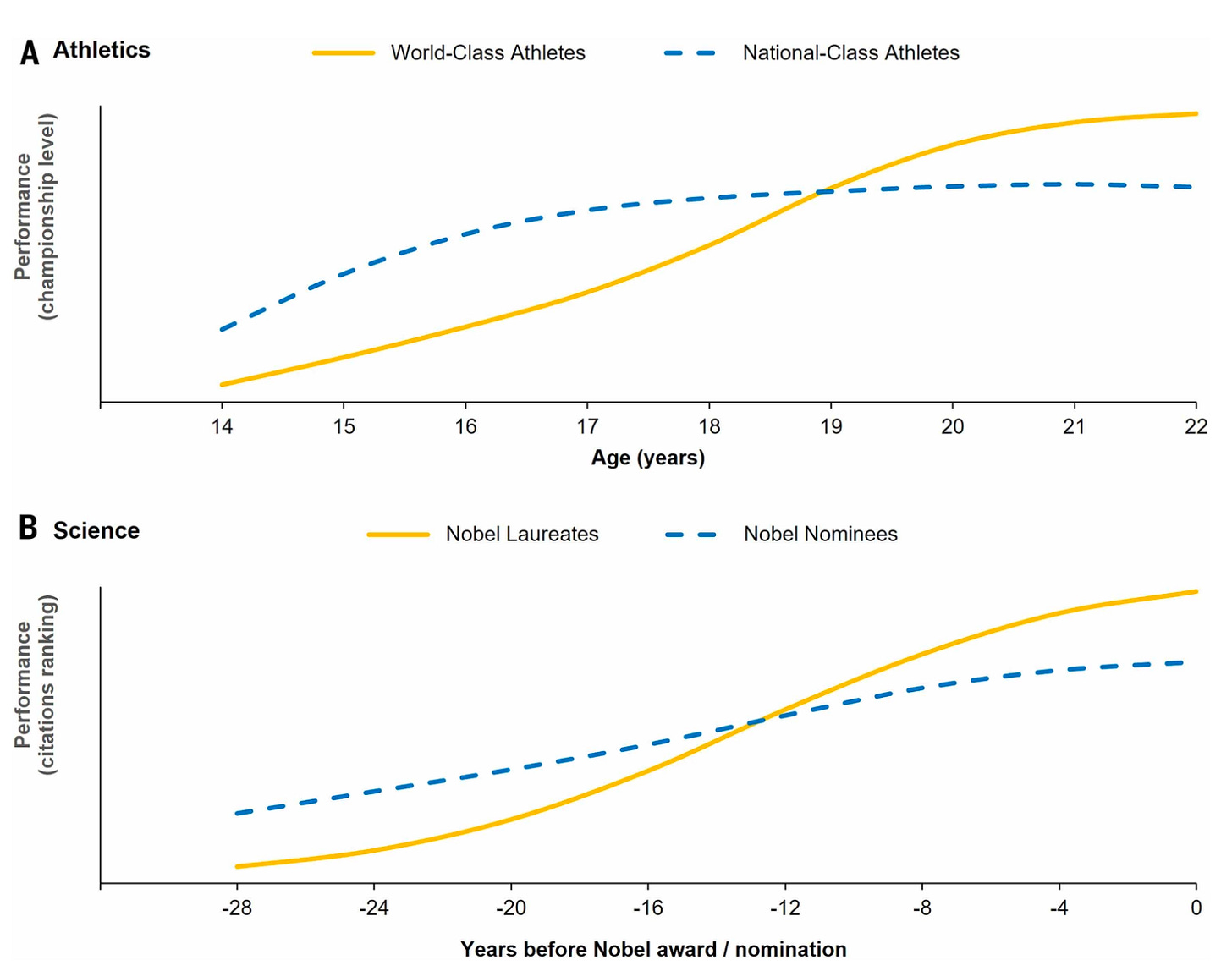

This figure shows the performance trajectories of the careers of world-class athletes and scientists compared to the trajectories of high performing but not elite performers within the same domains:

As you can see, in both athletics and science, the best performers at peak performance age— compared to their less-performing counterparts— showed lower performance in their early years. Put another way, eventual peak performance is negatively correlated with early performance.

Higher-performing junior athletes tended to start their respective main sport at younger ages, entered talent promotion programs at younger ages, and reached performance “milestones” at younger ages. In contrast, senior world-class athletes tended to start their main sport at older ages, enter talent promotion programs at older ages, and reached performance “milestone” at older ages.

Multidisciplinary Practice is Key

The same pattern was found when it comes to types and amounts of practice. Higher-performing junior athletes (compared with lower-performing junior athletes) racked up greater amount of practice in their main sport, but less practice in other sports. In contrast, senior world-class athletes (compared with lower-performing senior national-class athletes) racked up smaller amounts of practice in their main sports but greater amounts of practice in other sports.

On average, senior world-class athletes engaged in two other sports over the course of 9 years during childhood and adolescence. These findings were found across all types of Olympic sports. A similar pattern was found in other domains such as chess, academic, and music. For example, Noble laureates in the sciences had slower progress in terms of publication impact during their early years than Nobel nominees. Nobel laureates were also less likely to obtain a scholarship and took longer to earn their first professorship than the highest National-level awardees. Also, Nobel laureates in the sciences (compared with national-level awardees) engaged in more multidisciplinary activities in terms of study, practice, and working experiences, both within science and outside of science (e.g., arts, music, etc.).

These findings dovetail nicely with Dean Simonton’s classic finding that the success of composers’ operas was negatively correlated with the number of genre-specific operas they had previously composed but was positively correlated with the number of previous compositions across all genres. This suggests that the previous diverse experiences of composers was a better predictor of their success than their specialization within a single genre. Similarly, Lu Liu and colleagues looked at “hot streaks” across multiple years and across artistic, cultural, and scientific careers and found that hot streaks were often preceded by a multiyear period of work in other disciplines, genres, or artistic styles. Also, these findings are consistent with the central thesis of David Epstein’s excellent book “Range”, which is that generalists triumph in a specialized world (the subtitle of his book).

To be clear, these findings don’t contradict the fact that across domains, many adult world-class performers engaged in considerable amounts of discipline-specific practice. Nevertheless, while early acceleration of performance was frequent among early exceptional performers, it was infrequent among adult world-class performers. The thing that much better characterized adult world-class performers was multidisciplinary practice.

Also, this finding doesn’t contradict the fact that early exceptional performers are more likely to become adult exceptional performers compared with the remainder of the population in a domain. For one, the number of young people who are not early top performers is much larger than those who are. For example, in sports, those who reach international junior championships (compared with the rest of the population) are 49 more times as likely to go on to reach international senior championships. However, the number of young athletes who do not reach international junior championships is much larger (greater than 99% of all athletes) than those who do not reach international junior championships (less than 1%). The majority of adult athletes who reach international senior championships (more than 70%) come from the group who do not reach international junior championships.

Big Implications

I think these findings have big implications for how we measure potential and nurture talent in young people. In a way, these findings are a validation of the central thesis of my 2013 book “Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined”, which is that we have it all wrong when it comes to identifying the best markers of “lifelong potential” in young people. I attempted to challenge the conventional wisdom about the childhood predictors of adult success and argued that we need to do a better job in appreciating neurodiversity and the importance of passion-related factors.

Along those lines, consider the developmental model of world-class expertise I proposed with Angela Duckworth in 2015. We argued that a more accurate understanding of how world-class expertise develops must take into account not just factors relating to “early talent” but also factors that influence cumulative effort over time— such as optimism, passion, inspiration, curiosity, goal commitment, need for achievement, self-efficacy, growth mindset, self-regulation, grit, self-discipline, self-control, conscientiousness, and grit. We argue that over time, these factors multiply and end up carrying much more weight than early indicators of talent.

Also, I agree with Arne Güllich and colleagues that an important step for those who are attempting to identify young people who possess the potential to achieve world-class performance in the long term is to consider indicators that go beyond early top performance. Above-average, but not top, early performance together with discipline-specific practice and considerable multidisciplinary practice are indicators of long-term exceptional potential. This may even require limiting the amount of discipline-specific practice while increasing multiyear multidisciplinary practice. For instance, gifted education teachers who select a gifted young physicist in their program may encourage their students to also enroll in other programs such as computer science, philosophy, literature, or dare I say— art history!

I am reminded of the famous story of the cellist Yo-Yo Ma who decided to go to Harvard and study several liberal arts subjects than take a conservatory approach. This allowed him to limit his musical performance for the time and focus on courses in everything from anthropology to German literature during his undergraduate years.

At the very least, people in charge of gifted education programs and elite training programs for youth should be aware that when selecting the top early performers for admission, their selected group only includes a minority of the future adult top achievers, while the majority of future top achievers are outside the selected group. This is why I’m a fan of global screening procedures (not just relying on nominations) and expanded criteria for selection.

Clearly, different factors predict early exceptional “promise” than what predicts exceptional adult peak performance. In fact, the factors may not only be different but may actually be at odds with each other. It’s time for our talent development programs to change in light of the abundance of evidence that contradicts their standard assumptions about who reaches the highest levels of performance.

Love these findings!!!! Thank you for sharing !

I hope studies like this will filter down to parents and schools so they quit pushing their little prodigies so hard. It'll be good for their mental health as well as their long-term success. Thank you for sharing this!